Grass-Fed vs Grain-Fed

Shopping for meat can bring a lot of buzzwords that might be confusing. There are two main types of beef to choose from, grain-fed and grass-fed. After processing, the beef can be labeled, and from there, dry-aged. It might be difficult to figure out why grain-fed or grass-fed matter, why they are different, and even if there are benefits to one over the other, so we will break down what these terms mean and when to choose which type of beef.

Cows raised for their meat start their lives the same, whether they will be grain-fed or grass-fed. They drink milk and eat grass until around 7 to 9 months, and then are either kept roaming for grass-fed or moved to feedlots to be grain-fed. Grain-fed cattle are then rapidly fattened with grain feed typically made from soy or corn, and occasionally supplemented with dried grasses. Grass-fed has returned to popularity in recent years and is fairly common practice in Australia for beef such as Australian wagyu. Grass-fed cattle take much longer to mature: up to 20 to 24 months for grass-fed compared to an average of 15 months for grain-fed.

Credit: Pure Black Grass Fed Angus

Credit: Pure Black Grass Fed Angus

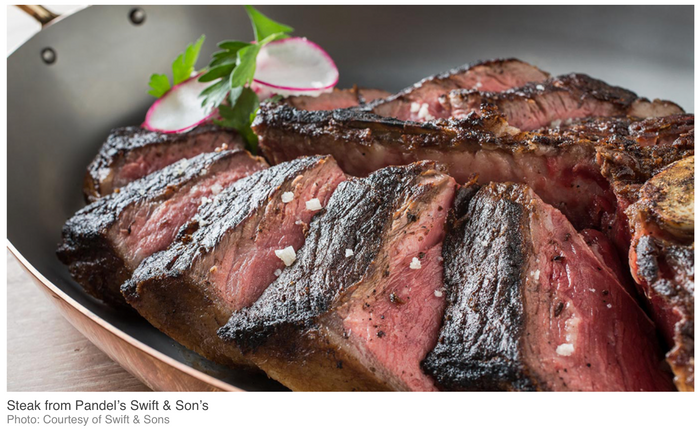

There are some differences to beef nutritionally depending on how the cattle are raised. Grass-fed beef tends to be leaner, with a richer or more pungent flavor. Grain-fed beef has a higher fat content and more marbling, which creates a fattier and more tender piece of beef, depending on the cut. Many people prefer the milder flavor of grain-fed beef to grass-fed as that is what they have been used to eating, but that can be totally up to personal preference. Choosing beef for the fat content is certainly necessary for some cuts of steak.

Grass-fed beef does tend to have slightly higher amounts of minerals, vitamins, and nutrients than its grain-fed counterpart, although in some cases the difference is minimal. Grass-fed beef is high in A, B, and E vitamins, creatine, and bioavailable iron; and eating beef helps keep iron levels up. Grass-fed beef also contains a higher content of Omega-3s and has much less monounsaturated fat than grain-fed. The differences in nutrients are usually low enough that the choice falls to flavor over vitamins and minerals.

Once the beef has been processed, it often goes through a grading system, with labels such as “USDA Super Prime,” which refer to the breed of cattle, the location, and the method used in raising the cattle. This grading system is primarily used in the United States and is optional for cattle ranchers. USDA Super Prime is the highest grade, judged on two metrics: the marbling and the maturity of the cattle. This grade has the highest amount of marbling and is considered the best quality meat. Only 0.04% of beef raised in the United States reaches this grade.

Grass-fed or grain-fed beef can both be dry-aged, which is a controlled-decay process of exposing the beef to oxygen, allowing it to break down which creates an incredibly tender and well-marbled cut of meat. Aged beef has a more concentrated beef flavor due to the moisture that has evaporated during the dry-aging process and the mouthfeel of the cut of beef becomes incredibly tender. Grass-fed beef will have an intense flavor, and the fattiness of grain-fed beef becomes accentuated in dry-aged steaks.

Credit: Stockyard Beef - Premium Australian Grain Fed Beef

Choosing the right cut of beef for your purpose becomes even more customized to your specific tastes when you take into consideration the way the beef was raised, the grade of the beef, and how it was aged. Your recipes can be taken to the next level with the right steak, and the tenderness of a dry-aged steak cannot be replicated with unaged beef - everyone will be raving about the melt-in-your-mouth texture and intense beef flavor.